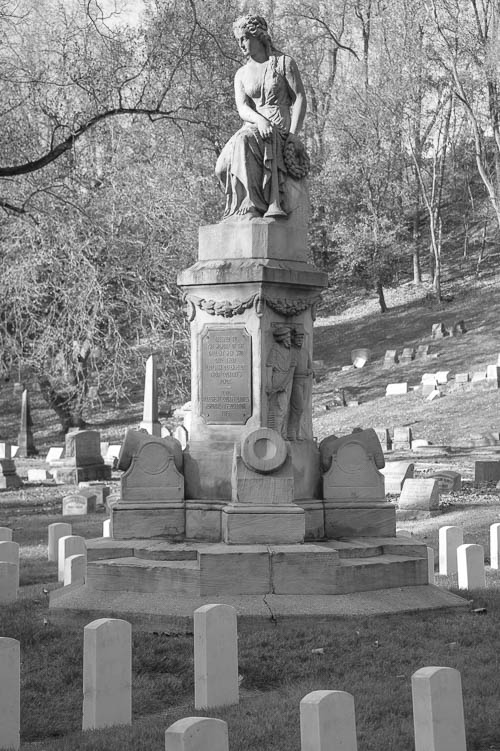

In 2018, I took a guided tour of Allegheny Cemetery. This cemetery is on the National Register of Historic places.

Allegheny Cemetery includes a National Cemetery Administration’s soldiers’ lot. The Allegheny Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot is located in Section 33 of Allegheny Cemetery. The majority of the 303 soldiers buried here were Civil War soldiers. Most of the burials were of Union soldiers; however, the lot also contains several Confederate soldiers.

I returned to the Soldiers’ Lot in 2019 in order to take some photos.

I didn’t have any prior knowledge of this following soldier, but I Googled his name when I returned home.

From the Veterans Affairs / website for Allegheny Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot: Corporal John M. Kendig (Civil War). He received the Medal of Honor while serving in the U.S. Army, Company A, 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry, for actions at Spotsylvania, Virginia, May 12, 1864. His citation was awarded under the name of Kindig. He died in 1869 and is buried in Section 33, Lot 66, Site 32.

Here’s a grave for an unknown Union (United States) Civil War soldier:

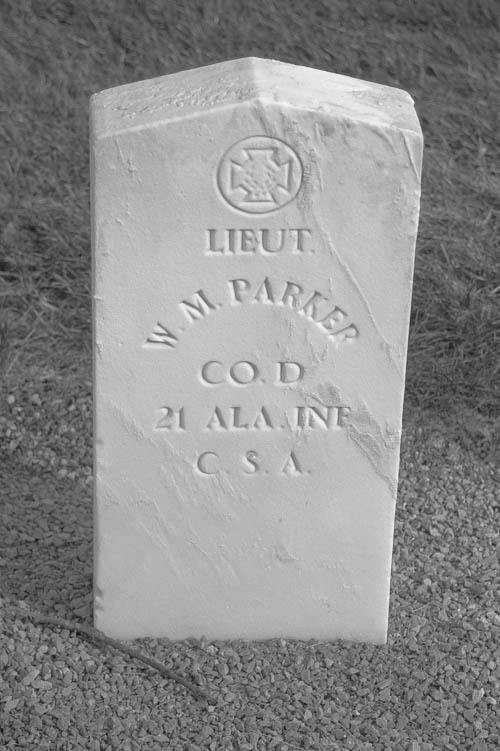

Finally, here is a Confederate grave that I saw at the Soldiers’ Lot. Note how the headstone differs from that of a Union soldier.